Farm & Ranch

[AgriLife Today] Beef cattle producers must be vigilant to mitigate herd health risks

By: Blair Fannin

Writer: Blair Fannin, 979-845-2259, [email protected]

Contacts: Dr. Joe Paschal, 361-265-9203, [email protected]

Dr. Tom Hairgrove, 979-845-5419, [email protected]

SAN ANTONIO – Beef cattle producers should be observant when conducting annual health vaccination protocols on their cattle, according to Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service experts.

Though not a statewide threat, the fever tick has resulted in some herds in far South Texas to be subject to a quarantine zone. This topic, as well as proper vaccination protocol and techniques, were discussed at the recent Texas and Southwestern Cattle Raisers Association Convention in San Antonio.

“It’s a one-host tick and we can use the cow as a control method. Right now, we can dip or spray the cow. If producers or veterinarians see ticks on cattle that are unusual, even if they are not, they are encouraged to collect those ticks and put them in a little bottle of isopropyl alcohol and send it to Texas Animal Health Commission veterinarians.”

Paschal said if they are identified as fever ticks, “we need to know where they are coming from and get a handle on them.”

“More than 99 percent of the time they are going to be common ticks, and we are going to know what they are,” he said. “There are some things to look for, and they are very easy to take off the animal. They are typically not very deep and not very colorful. When you pull a tick off and put it in your hand, it starts crawling off pretty fast. These ticks do not. They are very slow.”

The technical name for Texas cattle fever is bovine babesiosis, which relates to the organisms that infect the red blood cells of cattle. It is their destruction of the red blood cells that results in anemia, fever and death.

To learn more, AgriLife Extension experts recommend using Tick App, a free smartphone application available at http://tickapp.tamu.edu, and the Texas Animal Health Commission’s website at http://www.tahc.texas.gov/regs/code.html for information on tick treatment options, tick quarantine and associated regulations, as well as the latest updates on current quarantines.

(Click here to listen or download audio report)

Meanwhile, because of a case in Florida, though now eradicated by animal health officials in that state, screwworm is still something producers should watch for. Dr. Tom Hairgrove, AgriLife Extension program coordinator for food and livestock systems in College Station, said watchfulness is key.

“We still need to be very observant,” Hairgrove said. “It’s a maggot and will feed on live flesh in animals. If you see maggots in a live animal, take some of those maggots, put them in isopropyl alcohol and send them to TAHC (veterinarians). We want to get ahead of it. With the Florida outbreak, it might have been around a while on some small animals and was missed. It could have been going on a lot longer than most people thought.”

Hairgrove said this helps with surveillance and helps keep a record of where the samples are coming from.”

Hairgrove said he also advises beef cattle producers to develop a relationship with a local veterinarian.

“Sit down with your local practitioner,” he said. “Develop a good herd health program. A vaccination is just like insurance. We are just trying to mitigate against risk.”

-30-

Find more stories, photos, videos and audio at http://today.agrilife.org

Farm & Ranch

What to expect when your cow’s expecting

Overweight cattle and cattle turned out on lush legumes with high concentration are at risk as well. In this case, an epidural anesthetic is usually necessary. The tissue will need to be replaced and sutured in place. Vaginal sutures will need to be removed prior to calving.

Toxemia happens when cattle are exposed to low nutrition during the last two months of pregnancy. Cows that are overly fat and/or carrying twins are at higher risk. Cows with toxemia become depressed, stop eating and often stand off away from the herd. You will notice some have the scent of acetone on their breath. As the condition worsens, the cow may develop muscle tremors. Treatment for toxemia is IV glucose, B vitamins or propylene glycol given by oral drench.

During calving there are a number of problems that could occur. Those include dystocia, bruises and lacerations to the birth canal, uterine prolapse, milk fever, retained placenta and grass tetany.

According to the Beef Cattle Handbook, a product of Extension Beef Cattle Resource Committee Adapted from the Cattle Producer’s Library, at any time a cow is unable to deliver her calf, a dystocia has occurred. There are many things a producer can do to reduce this incidence. With heifers, lot those with small pelvic areas before breeding. Select bulls based on their birth weight, not on their relative size. Ultimately use bulls that will produce small birth-weight calves. When calving first-calf heifers separate them from cows, at best into small groups. Producers will want to provide surveillance over the heifers on a 24 hour basis. Some tips include restricting the calving to 42 to 60 days. That will enable personal focus for a short, intense calving period. Also feeding at night between 9 and 11 p.m. will cause more animals to calve during daylight hours.

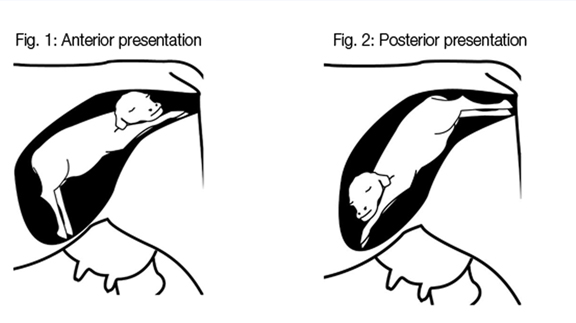

If problems arise and a cow hasn’t shown progress in 60 to 90 minutes, it’s time for the producers to step in. Signs of an abnormal delivery are the head only, the head and one leg, one leg alone or the tail. At this point it is best to contain the animal in a squeeze chute or small pen. A calf can only deliver one of two ways: both front feet followed by the head or both back feet out together. Once constrained, using ample lubrication, a producer can reach in and move the calf to one of the two correct positions. If unable to do so, a veterinarian should be called. The top problems include not getting the head out with front feet, having a calf too big to deliver through the mother’s birth canal resulting in hip lock and abnormal breach in which the tail is the only part of the calf visible through the vulva. If all goes well and pulling the calf is suggested, direct traction down and away from the birth canal. Do not pull straight out behind the cow. If two men are unable to pull the calf using the OB chains or when using the calf puller, do not use excessive force. It will not deliver the calf. Odds are the cows birth canal is too small for the calf and will result in a c-section.

Keep in mind bruises, lacerations and rupture of the birth canal are possible during a difficult birth. Rough handling of the calf or maternal tissues and careless use of obstetrical instruments during calving add danger. This is typical when a cow is in labor several hours with a dry, non-lubricated birth canal.

Cows with difficult delivery and trauma to the tissue and birth canal may have damage to the nerves and spinal cord or hips that supply the legs. This results in abnormal leg function. In some cases, while pulling a calf, excessive force was used and the middle lower pelvis bones were fractured. At this point steroids are administered to help with swelling and nerve healing. In bad cases were the cows are unable to stand, they need to be hoisted to their feet twice a day.

In older cows producers may see difficulty in birth injury or irritation of the external birth canal and severe straining, retained placenta and loose uterine attachment in the abdominal cavity called uterine prolapse. When noticed, this condition needs immediate action. Apply material to uterine wall to saturate fluid ASAP. You can use sulfaurea powder, urea powder or even sugar. Replace the uterus immediately or call your veterinarian. Without properly replacing the uterine horns, prolapse will reoccur.

Usually the placenta is passed in three to eight hours. If the placenta hasn’t passed in eight to 12 hours of calving, the placenta is retained and the cows must be treated. A number of reasons lead to retained placenta: dystocia, c-sections, fetotomy, twinning or abortion along with other infectious diseases. Even feed deficiencies, malnutrition, low carotene, vitamin A, iodine, selenium and vitamin E can be to blame. To treat, use slight, manual force and gently pull on the placenta. If it resists, stop and pack the uterus with boluses or fluid douches to keep antibiotics in the uterus. As with prolapse, be sure to use proper hygiene when treating the uterus or worse problems will occur.

Another condition parallel with cows with age, number of calves and dairy or mixed breeds is milk fever. This condition happens when a cow starting to produce milk is unable to remove calcium from her bones quickly enough. If blood levels of calcium fall below the minimal level, the muscles of the body are unable to function. This leaves the cow almost crippled, comatose and dead. High blood levels of estrogen inhibit calcium mobilization; this may be a factor on pastures that are high in legumes. Usually a slow administer of IV calcium is given. 300 to 500 ml of a commercial calcium solution is given over 20 to 30 minutes.

Lastly, grass tetany poses as an issue to cows calving. It is similar to milk fever, but in this instance cattle have heavy post-calving lactation and lose large amounts of magnesium in their milk. Most types of mixed pasture grasses are low in magnesium. If cows are exposed to cold weather or stress during early lactation, their blood levels may drop low enough to cause grass tetany. At that point an IV of magnesium is given with calcium. Treatment is not as effective as with milk fever and in many cases, animals do not respond.

This article was originally published in the January 2016 issue of North Texas Farm & Ranch.

Farm & Ranch

Managing Show Cattle Through The Winter

By Heather Welper

Husband and wife duo, Heather and Calvin Welper, are the Co-Owners and Operators or Two C Livestock, located in Valley View, Texas.

The pair’s operation has a show cattle focus where they raise and sell purebred heifers of all breeds and club calf Hereford steers.

When it comes to show cattle, the Welpers know a thing or two including how to prepare for the cold winter months and the Texas major show season run.

To read more, pick up a copy of the November edition of North Texas Farm & Ranch magazine, available digitally and in print. To subscribe by mail, call 940-872-5922.

Farm & Ranch

Double M Ranch & Rescue

By Hannah Claxton, Editor

As the sun rises each day, so do the dozens of mouths that Meghan McGovern is responsible for getting fed. Rather than the sounds of a rooster crowing, McGovern hears the bellows and bleats of a variety of exotic deer, the chortle of kangaroos, the grunts of water buffaloes, and the chirps of a lemur.

Nestled against the banks of the Red River, the Double M Ranch and Rescue, with its high game fences and deer sprinkling the landscape,s its in stark contrast to the surrounding ranches.

“Having deer is kind of like eating potato chips- you can never actually have just one,” said McGovern with a laugh.

McGovern has several herds to take care of- fallow deer, axis deer, water buffalo, goats, and bison. In smaller numbers, there’s also a few kangaroos, a lemur, a potbelly pig, a pair of zebras, a watusi, and a few horses.

To read more, pick up a copy of the November edition of North Texas Farm & Ranch magazine, available digitally and in print. To subscribe by mail, call 940-872-5922.

-

Country Lifestyles2 years ago

Country Lifestyles2 years agoScott & Stacey Schumacher: A Growth Mindset

-

Country Lifestyles8 years ago

Country Lifestyles8 years agoStyle Your Profile – What your style cowboy hat says about you and new trends in 2017

-

HOME8 years ago

HOME8 years agoGrazing North Texas – Wilman Lovegrass

-

Outdoor10 years ago

Outdoor10 years agoButtercup or Primrose?

-

Country Lifestyles5 years ago

Country Lifestyles5 years agoAmber Crawford, Breakaway Roper

-

Country Lifestyles9 years ago

Country Lifestyles9 years agoJune 2016 Profile – The man behind the mic: Bob Tallman

-

Country Lifestyles8 years ago

Country Lifestyles8 years agoDecember 2016 Profile, Rusty Riddle – The Riddle Way

-

Equine1 year ago

Equine1 year agoThe Will to Win