Farm & Ranch

[AgriLife Today] Bacteria battle: How one changes appearance, moves away to resist the other

By: Kathleen Phillips

- Writer: Kathleen Phillips, 979-845-2872, [email protected]

- Contact: Dr. Paul Straight, 979-845-1012, [email protected]

COLLEGE STATION — Two types of bacteria found in the soil have enabled scientists at Texas A&M AgriLife Research to get the dirt on how resistance to antibiotics develops along with a separate survival strategy.

The study, published in the journal PLoS Genetics this month, identifies an atypical antibiotic molecule and the way in which the resistance to that molecule arises, including the identity of the genes that are responsible, according to Dr. Paul Straight, AgriLife Research biochemist.

Straight and his doctoral student Reed Stubbendieck observed a species of bacteria changing its appearance and moving away from a drug to avoid being killed.

Straight’s lab on the Texas A&M University campus in College Station in general focuses on understanding how communities of bacteria interact with each other and other microbes.

“Over the past few decades, scientists have come to understand that bacteria aren’t just single individual cells that somehow cause infections or degrade toxins, for example,” Straight said. “In fact, they are populations and communities of many, many cells, whether just a si

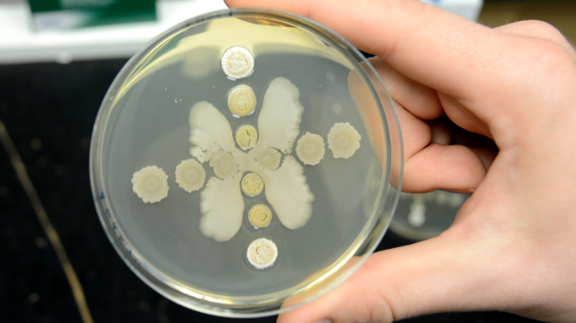

Two types of bacteria found in the soil have enabled scientists at Texas A&M AgriLife Research to get the dirt on how resistance to antibiotics develops along with a separate survival strategy. (Texas A&M AgriLife photo by Kathleen Phillips)

ngle species of bacteria or a very diverse community. We are most recently aware of this in terms of the human microbiome. People have more bacteria cells in them than they have human cells.”

Reed Stubbendieck, Texas A&M University graduate student. (Texas A&M AgriLife photo by Kathleen Phillips)

But what has not been fully understood about bacteria and microbes in general, he said, is the way in which they form these types of communities with more than one species.

“It’s both an ecological and a mechanistic bacteriology question,” Straight said. “For nearly 100 years, we’ve known that bacteria can produce molecules that can block the growth of other organisms including other bacteria, and those molecules have been very useful as antibiotics.”

Straight said the common understanding of the usefulness of antibiotics, however, sidestepped the ecological dynamics of the bacteria themselves in how they form communities, and interact with each other.

“We wanted to know what happens when we put two bacterial species together to compete with each other and use that model as a way to identify new molecules, identify pathways, or gene functions, that are required for the bacteria to survive under competitive stress,” he explained. “Identification of interesting new molecules or bacterial mechanisms of control that one might exploit can lead to developing a new antibiotic.”

For this study, Stubbendieck put together two species of non-pathogenic, soil-borne bacteria, Streptomyces and Bacillus subtilis, in different ways in the laboratory. He monitored the bacteria for different patterns in growth, motility and other factors when the organisms were together as opposed to when they were separate.

Stubbendieck noticed that the two bacteria would grow as expected in each colony initially, but over time one of the bacteria colonies would start to destroy the other one.

“It was very visual,” Straight said. “It would cause lysis, meaning that the cells inside the dying colony would be dissolved, leaving a mark of where this had happened.”

Stubbendieck had to identify the molecule or other functions that are responsible for causing the destruction, thus the way in which resistance might emerge.

“The molecule turned out to be very strange. It doesn’t look like any of the familiar antibiotics,” Straight said. “We find it interesting, because its chemical structure suggests it’s probably functioning in a way that is very different from the common antibiotics that are used.”

Stubbendieck also noted that in the region where the cells were destroyed, there developed “little teeny colonies of bacteria” growing, indicating that they’re resistant to the molecule. So he picked a number of those colonies and sequenced the genomes, which found the mutations that cause resistance.

“I put a bunch of the cells with mutant bacterial stains on a petri dish together, and when I came in the next morning and looked in the incubator, I saw a difference between the mutants and the non-mutant strain that was night and day, and we knew we are on to something,” Stubbendieck recalled.

“With two pieces of the puzzle — the molecule itself identified plus a way in which the resistance to that molecule would arise, including the identity of the genes that are responsible for resistance — Reed was able to dissect the pathway of resistance,” Straight said. “And it turns out that in a B. subtilis membrane, proteins work as signaling systems for lots of different things. They can receive signals from the external environment, signals from other bacteria, signals telling them about the status of their cell in a fluctuating environment.

“If something damages a membrane, bacteria have a way of sensing that and then turning on the response,” Straight said.

All of the mutations Stubbendieck identified were in the same gene that encodes for a protein in the membrane that functions like a signaling protein, or it has a partner that it talks to, and all mutations turned on the signaling system. And, because the mutants had proteins that were turned on all the time, the drug that previously would have been effective could no longer kill the bacteria.

Additionally, not only did the researchers see that resistance could emerge that way but also the population of the B. subtilis, the one that’s typically killed by the drug, changed in appearance.

“It had morphological shapes and structures to it, which suggested that this organism had undergone a really profound change. That allowed it not only to be resistant to this drug, which causes lysis, but also to move as a population of bacteria across the agar surface in a petri dish,” Straight said.

“This shows a way that organisms can interact with each other in a competitive, dynamic environment that’s very different from the way we typically think about antibiotics,” he added. “It is not just a simple, one-way street of a molecule that’s produced and causes growth inhibition of the pathogen, and the pathogen can become resistant and that might be a problem for health reasons. What we’re seeing here are molecules that can function like an antibiotic and cause something like lysis, or cell death. And the organisms can use not just one resistance function but a combination of responses as a way of circumventing a competitive crisis.”

“This helps scientists build a much more mechanistically detailed picture of the competitive dynamics between bacteria, which helps us understand what happens in soil or inside a human intestine,” Straight added. “It helps us start to get a better image to work from when we talk about the role of microbes in the environment and the way competitive interactions structure microbial communities; how something becomes resistant and therefore how we might control that.”

-30-

Find more stories, photos, videos and audio at http://today.agrilife.org

Farm & Ranch

What to expect when your cow’s expecting

Overweight cattle and cattle turned out on lush legumes with high concentration are at risk as well. In this case, an epidural anesthetic is usually necessary. The tissue will need to be replaced and sutured in place. Vaginal sutures will need to be removed prior to calving.

Toxemia happens when cattle are exposed to low nutrition during the last two months of pregnancy. Cows that are overly fat and/or carrying twins are at higher risk. Cows with toxemia become depressed, stop eating and often stand off away from the herd. You will notice some have the scent of acetone on their breath. As the condition worsens, the cow may develop muscle tremors. Treatment for toxemia is IV glucose, B vitamins or propylene glycol given by oral drench.

During calving there are a number of problems that could occur. Those include dystocia, bruises and lacerations to the birth canal, uterine prolapse, milk fever, retained placenta and grass tetany.

According to the Beef Cattle Handbook, a product of Extension Beef Cattle Resource Committee Adapted from the Cattle Producer’s Library, at any time a cow is unable to deliver her calf, a dystocia has occurred. There are many things a producer can do to reduce this incidence. With heifers, lot those with small pelvic areas before breeding. Select bulls based on their birth weight, not on their relative size. Ultimately use bulls that will produce small birth-weight calves. When calving first-calf heifers separate them from cows, at best into small groups. Producers will want to provide surveillance over the heifers on a 24 hour basis. Some tips include restricting the calving to 42 to 60 days. That will enable personal focus for a short, intense calving period. Also feeding at night between 9 and 11 p.m. will cause more animals to calve during daylight hours.

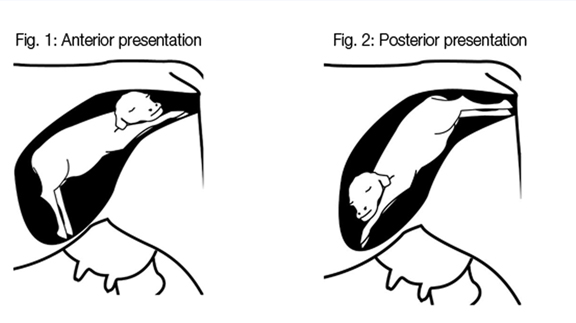

If problems arise and a cow hasn’t shown progress in 60 to 90 minutes, it’s time for the producers to step in. Signs of an abnormal delivery are the head only, the head and one leg, one leg alone or the tail. At this point it is best to contain the animal in a squeeze chute or small pen. A calf can only deliver one of two ways: both front feet followed by the head or both back feet out together. Once constrained, using ample lubrication, a producer can reach in and move the calf to one of the two correct positions. If unable to do so, a veterinarian should be called. The top problems include not getting the head out with front feet, having a calf too big to deliver through the mother’s birth canal resulting in hip lock and abnormal breach in which the tail is the only part of the calf visible through the vulva. If all goes well and pulling the calf is suggested, direct traction down and away from the birth canal. Do not pull straight out behind the cow. If two men are unable to pull the calf using the OB chains or when using the calf puller, do not use excessive force. It will not deliver the calf. Odds are the cows birth canal is too small for the calf and will result in a c-section.

Keep in mind bruises, lacerations and rupture of the birth canal are possible during a difficult birth. Rough handling of the calf or maternal tissues and careless use of obstetrical instruments during calving add danger. This is typical when a cow is in labor several hours with a dry, non-lubricated birth canal.

Cows with difficult delivery and trauma to the tissue and birth canal may have damage to the nerves and spinal cord or hips that supply the legs. This results in abnormal leg function. In some cases, while pulling a calf, excessive force was used and the middle lower pelvis bones were fractured. At this point steroids are administered to help with swelling and nerve healing. In bad cases were the cows are unable to stand, they need to be hoisted to their feet twice a day.

In older cows producers may see difficulty in birth injury or irritation of the external birth canal and severe straining, retained placenta and loose uterine attachment in the abdominal cavity called uterine prolapse. When noticed, this condition needs immediate action. Apply material to uterine wall to saturate fluid ASAP. You can use sulfaurea powder, urea powder or even sugar. Replace the uterus immediately or call your veterinarian. Without properly replacing the uterine horns, prolapse will reoccur.

Usually the placenta is passed in three to eight hours. If the placenta hasn’t passed in eight to 12 hours of calving, the placenta is retained and the cows must be treated. A number of reasons lead to retained placenta: dystocia, c-sections, fetotomy, twinning or abortion along with other infectious diseases. Even feed deficiencies, malnutrition, low carotene, vitamin A, iodine, selenium and vitamin E can be to blame. To treat, use slight, manual force and gently pull on the placenta. If it resists, stop and pack the uterus with boluses or fluid douches to keep antibiotics in the uterus. As with prolapse, be sure to use proper hygiene when treating the uterus or worse problems will occur.

Another condition parallel with cows with age, number of calves and dairy or mixed breeds is milk fever. This condition happens when a cow starting to produce milk is unable to remove calcium from her bones quickly enough. If blood levels of calcium fall below the minimal level, the muscles of the body are unable to function. This leaves the cow almost crippled, comatose and dead. High blood levels of estrogen inhibit calcium mobilization; this may be a factor on pastures that are high in legumes. Usually a slow administer of IV calcium is given. 300 to 500 ml of a commercial calcium solution is given over 20 to 30 minutes.

Lastly, grass tetany poses as an issue to cows calving. It is similar to milk fever, but in this instance cattle have heavy post-calving lactation and lose large amounts of magnesium in their milk. Most types of mixed pasture grasses are low in magnesium. If cows are exposed to cold weather or stress during early lactation, their blood levels may drop low enough to cause grass tetany. At that point an IV of magnesium is given with calcium. Treatment is not as effective as with milk fever and in many cases, animals do not respond.

This article was originally published in the January 2016 issue of North Texas Farm & Ranch.

Farm & Ranch

Managing Show Cattle Through The Winter

By Heather Welper

Husband and wife duo, Heather and Calvin Welper, are the Co-Owners and Operators or Two C Livestock, located in Valley View, Texas.

The pair’s operation has a show cattle focus where they raise and sell purebred heifers of all breeds and club calf Hereford steers.

When it comes to show cattle, the Welpers know a thing or two including how to prepare for the cold winter months and the Texas major show season run.

To read more, pick up a copy of the November edition of North Texas Farm & Ranch magazine, available digitally and in print. To subscribe by mail, call 940-872-5922.

Farm & Ranch

Double M Ranch & Rescue

By Hannah Claxton, Editor

As the sun rises each day, so do the dozens of mouths that Meghan McGovern is responsible for getting fed. Rather than the sounds of a rooster crowing, McGovern hears the bellows and bleats of a variety of exotic deer, the chortle of kangaroos, the grunts of water buffaloes, and the chirps of a lemur.

Nestled against the banks of the Red River, the Double M Ranch and Rescue, with its high game fences and deer sprinkling the landscape,s its in stark contrast to the surrounding ranches.

“Having deer is kind of like eating potato chips- you can never actually have just one,” said McGovern with a laugh.

McGovern has several herds to take care of- fallow deer, axis deer, water buffalo, goats, and bison. In smaller numbers, there’s also a few kangaroos, a lemur, a potbelly pig, a pair of zebras, a watusi, and a few horses.

To read more, pick up a copy of the November edition of North Texas Farm & Ranch magazine, available digitally and in print. To subscribe by mail, call 940-872-5922.

-

Country Lifestyles2 years ago

Country Lifestyles2 years agoScott & Stacey Schumacher: A Growth Mindset

-

Country Lifestyles8 years ago

Country Lifestyles8 years agoStyle Your Profile – What your style cowboy hat says about you and new trends in 2017

-

HOME8 years ago

HOME8 years agoGrazing North Texas – Wilman Lovegrass

-

Outdoor10 years ago

Outdoor10 years agoButtercup or Primrose?

-

Country Lifestyles5 years ago

Country Lifestyles5 years agoAmber Crawford, Breakaway Roper

-

Country Lifestyles8 years ago

Country Lifestyles8 years agoDecember 2016 Profile, Rusty Riddle – The Riddle Way

-

Country Lifestyles9 years ago

Country Lifestyles9 years agoJune 2016 Profile – The man behind the mic: Bob Tallman

-

Equine1 year ago

Equine1 year agoThe Will to Win