Farm & Ranch

[AgriLife Today] Texas Native Seeds project expanding to meet demand ecosystem restoration

By: Adam Russell

- Writer: Adam Russell, 903-834-6191, [email protected]

- Contact: Forrest Smith, 361-593-4525, [email protected]

- Dr. Jim Muir, 254-968-4144, [email protected]

STEPHENVILLE – The statewide search for seeds from native Texas grasses and forbs is expected to expand to East Texas in 2018, according to Texas A&M researchers.

Hooded windmillgrass seed-increase harvest at the Texas A&M AgriLife Research and Extension Center in Stephenville. (Texas A&M AgriLife Research photo by Randy Bow)

Forrest Smith, the Dan L. Duncan Endowed director of the Texas Native Seeds project for the Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute at Texas A&M University-Kingsville, said the interest in re-establishment of native grasses and forbs is growing, and research initiatives are expanding.

“The vision (of Texas Native Seeds) is to find and collect important native plant species and increase them to meet demand for restoration,” he said.

Texas A&M AgriLife Research and Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service has provided staff expertise, in-kind access to facilities, field space and equipment at Texas A&M Research and Extension Centers in Corpus Christi and Stephenville in support of that mission.

AgriLife Research scientists have been close cooperators on several restoration methodology projects as the native seed project began its statewide expansion in 2010. Texas A&M’s Texas Foundation Seed Service, meanwhile, certifies and licenses the project’s native seeds to make them available to the public.

Smith said the project started in 2000 in South Texas after private landowners with major holdings approached the institute looking for ways to re-establish native grasses and forbs, restoring regional ecosystems that support native wildlife.

Researchers are seeking to increase a diverse seed mix of native species to provide to seed companies for production, Smith said. The native seeds would be for commercial production to keep up with demand. They would be maintained in a species database available for future research.

Seeds are collected from specific locations, and information, such as soil type and adjacent species, are recorded, Smith said. Researchers collected around 1,200 native plant species in

West Texas and around 750 species in Central Texas in the past few years, on top of over 2,000 seed collections made since 2001 in South Texas.

Similar efforts in other parts of the state will be undertaken in 2018, he said.

The native plants are being grown and evaluated for specific traits including survivability, germination, aesthetics and seed production, Smith said. Seed mixes and individual seed varieties will be certified and released through Texas Foundation Seed Service once the evaluation process is complete.

Smith said seeds from the various regions of Texas are being sought because species’ traits can differ in such a large and ecologically diverse state.

For instance, little bluestem, a prolific warm-season perennial grass, grows from Canada to Mexico, Smith said. Seeds from this species in Canada differ greatly from those found in Texas, because the plants’ internal schedules, such as seeding, differ.

A Texas little bluestem may produce seed later in the year because of warmer environmental conditions, he said. Texas little bluestem would face low survivability if its seeds faced earlier wintry weather in Canada.

Smith said many commercial native seeds are available to the public, but it is crucial to local ecosystems that researchers find the best suited native plants for Texas and high-quality seeds are made available to consumers.

“Much of the available native seed sold in Texas today is not regionally adapted to the areas it is used in, and furthermore, there are quality concerns with some of that material.”

The initial project, South Texas Natives, received a boost of funding in 2010 when the Texas Department of Transportation provided a substantial grant to facilitate expansion of the effort into Central and West Texas, Smith said. Landowners and industry, especially utility and petroleum companies, also support and collaborate with the effort.

TxDOT views native grasses and forbs, especially low-growing species, as a way to reduce roadside maintenance costs, such as mowing, compared to exotic species that have been introduced, such as Coastal Bermuda grass or johnsongrass.

“They saw it as a way to potentially reduce the number of times they have to mow each year and to sustain diversity,” he said.

TxDOT has been able to change their seeding specifications for rural areas in two-thirds of Texas because of the program, Smith said.

Smith said TxDOT continues to support the effort and the Texas Native Seeds project is expected to expand into East Texas next year. Supporters in East Texas have shown great interest in the program, led by Ellen Temple, a landowner and supporter of the program from Lufkin.

In 2017, the program expanded to the booming Permian Basin region, through support provided by Concho Resources, a Midland-based oil and gas company. As a result of energy development, demand for native seeds and restoration in this region is high, Smith said.

Texas A&M AgriLife Research in Stephenville has been an integral partner in the Central Texas effort, Smith said. Other vital cooperators include the U.S. Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service Plant Materials Centers in Kingsville and Knox City, Tarleton State University and Sul Ross State University’s Borderlands Research Institute.

Commercial seed companies are also very important partners in the program, Smith said. Douglass King Seed Company, San Antonio, has been a long-time licensee for seed production, and more recently, Bamert Seed Company, Muleshoe, has also started producing seed selections made through Texas Native Seeds.

Dr. Jim Muir, AgriLife Research grassland ecologist, Stephenville, said there is a growing movement among landowners and within industry to reintroduce native plant species in order to re-establish ecosystems that have been disturbed by invasive species.

“We’re seeing more people who own land or who are returning to the homes they grew up in who aren’t involved in agriculture or interested in producing one more calf on Bermuda grass,” he said. “They’re concerned about returning pastures back to native grasses to get plants that attract and support native wildlife, such as songbirds, deer, quail and pollinators.

“Bermuda grasses are an ecological desert in terms of wildlife and pollinators, whereas native plants support an entire ecosystem.”

Plants, such as legumes, provide nitrogen for the soil, Muir said. They also provide feed for animals and insects, and seeds for birds and mice which provide food for predators such as fox, hawks and owls. Legumes also flower at different times of the year, which attracts and supports pollinators, such as butterflies.

“It’s becoming more-and-more prevalent that landowners don’t see themselves simply as farmers and ranchers but, rather, stewards of the land,” Muir said. “These stewards are looking for the native seed mixes that Texas Native Seeds Project provides.”

For more information about Texas Native Seeds, go to http://bit.ly/2z4QnFE or contact Smith at 361-593-4525 or [email protected].

-30-

Find more stories, photos, videos and audio at http://today.agrilife.org

Farm & Ranch

What to expect when your cow’s expecting

Overweight cattle and cattle turned out on lush legumes with high concentration are at risk as well. In this case, an epidural anesthetic is usually necessary. The tissue will need to be replaced and sutured in place. Vaginal sutures will need to be removed prior to calving.

Toxemia happens when cattle are exposed to low nutrition during the last two months of pregnancy. Cows that are overly fat and/or carrying twins are at higher risk. Cows with toxemia become depressed, stop eating and often stand off away from the herd. You will notice some have the scent of acetone on their breath. As the condition worsens, the cow may develop muscle tremors. Treatment for toxemia is IV glucose, B vitamins or propylene glycol given by oral drench.

During calving there are a number of problems that could occur. Those include dystocia, bruises and lacerations to the birth canal, uterine prolapse, milk fever, retained placenta and grass tetany.

According to the Beef Cattle Handbook, a product of Extension Beef Cattle Resource Committee Adapted from the Cattle Producer’s Library, at any time a cow is unable to deliver her calf, a dystocia has occurred. There are many things a producer can do to reduce this incidence. With heifers, lot those with small pelvic areas before breeding. Select bulls based on their birth weight, not on their relative size. Ultimately use bulls that will produce small birth-weight calves. When calving first-calf heifers separate them from cows, at best into small groups. Producers will want to provide surveillance over the heifers on a 24 hour basis. Some tips include restricting the calving to 42 to 60 days. That will enable personal focus for a short, intense calving period. Also feeding at night between 9 and 11 p.m. will cause more animals to calve during daylight hours.

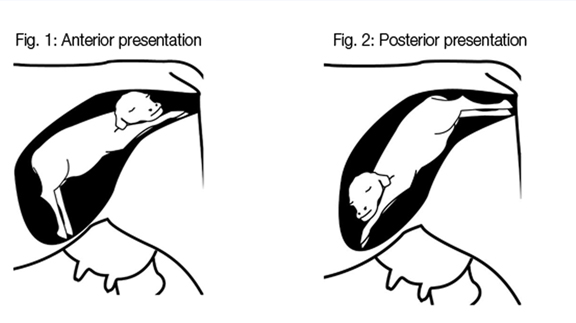

If problems arise and a cow hasn’t shown progress in 60 to 90 minutes, it’s time for the producers to step in. Signs of an abnormal delivery are the head only, the head and one leg, one leg alone or the tail. At this point it is best to contain the animal in a squeeze chute or small pen. A calf can only deliver one of two ways: both front feet followed by the head or both back feet out together. Once constrained, using ample lubrication, a producer can reach in and move the calf to one of the two correct positions. If unable to do so, a veterinarian should be called. The top problems include not getting the head out with front feet, having a calf too big to deliver through the mother’s birth canal resulting in hip lock and abnormal breach in which the tail is the only part of the calf visible through the vulva. If all goes well and pulling the calf is suggested, direct traction down and away from the birth canal. Do not pull straight out behind the cow. If two men are unable to pull the calf using the OB chains or when using the calf puller, do not use excessive force. It will not deliver the calf. Odds are the cows birth canal is too small for the calf and will result in a c-section.

Keep in mind bruises, lacerations and rupture of the birth canal are possible during a difficult birth. Rough handling of the calf or maternal tissues and careless use of obstetrical instruments during calving add danger. This is typical when a cow is in labor several hours with a dry, non-lubricated birth canal.

Cows with difficult delivery and trauma to the tissue and birth canal may have damage to the nerves and spinal cord or hips that supply the legs. This results in abnormal leg function. In some cases, while pulling a calf, excessive force was used and the middle lower pelvis bones were fractured. At this point steroids are administered to help with swelling and nerve healing. In bad cases were the cows are unable to stand, they need to be hoisted to their feet twice a day.

In older cows producers may see difficulty in birth injury or irritation of the external birth canal and severe straining, retained placenta and loose uterine attachment in the abdominal cavity called uterine prolapse. When noticed, this condition needs immediate action. Apply material to uterine wall to saturate fluid ASAP. You can use sulfaurea powder, urea powder or even sugar. Replace the uterus immediately or call your veterinarian. Without properly replacing the uterine horns, prolapse will reoccur.

Usually the placenta is passed in three to eight hours. If the placenta hasn’t passed in eight to 12 hours of calving, the placenta is retained and the cows must be treated. A number of reasons lead to retained placenta: dystocia, c-sections, fetotomy, twinning or abortion along with other infectious diseases. Even feed deficiencies, malnutrition, low carotene, vitamin A, iodine, selenium and vitamin E can be to blame. To treat, use slight, manual force and gently pull on the placenta. If it resists, stop and pack the uterus with boluses or fluid douches to keep antibiotics in the uterus. As with prolapse, be sure to use proper hygiene when treating the uterus or worse problems will occur.

Another condition parallel with cows with age, number of calves and dairy or mixed breeds is milk fever. This condition happens when a cow starting to produce milk is unable to remove calcium from her bones quickly enough. If blood levels of calcium fall below the minimal level, the muscles of the body are unable to function. This leaves the cow almost crippled, comatose and dead. High blood levels of estrogen inhibit calcium mobilization; this may be a factor on pastures that are high in legumes. Usually a slow administer of IV calcium is given. 300 to 500 ml of a commercial calcium solution is given over 20 to 30 minutes.

Lastly, grass tetany poses as an issue to cows calving. It is similar to milk fever, but in this instance cattle have heavy post-calving lactation and lose large amounts of magnesium in their milk. Most types of mixed pasture grasses are low in magnesium. If cows are exposed to cold weather or stress during early lactation, their blood levels may drop low enough to cause grass tetany. At that point an IV of magnesium is given with calcium. Treatment is not as effective as with milk fever and in many cases, animals do not respond.

This article was originally published in the January 2016 issue of North Texas Farm & Ranch.

Farm & Ranch

Managing Show Cattle Through The Winter

By Heather Welper

Husband and wife duo, Heather and Calvin Welper, are the Co-Owners and Operators or Two C Livestock, located in Valley View, Texas.

The pair’s operation has a show cattle focus where they raise and sell purebred heifers of all breeds and club calf Hereford steers.

When it comes to show cattle, the Welpers know a thing or two including how to prepare for the cold winter months and the Texas major show season run.

To read more, pick up a copy of the November edition of North Texas Farm & Ranch magazine, available digitally and in print. To subscribe by mail, call 940-872-5922.

Farm & Ranch

Double M Ranch & Rescue

By Hannah Claxton, Editor

As the sun rises each day, so do the dozens of mouths that Meghan McGovern is responsible for getting fed. Rather than the sounds of a rooster crowing, McGovern hears the bellows and bleats of a variety of exotic deer, the chortle of kangaroos, the grunts of water buffaloes, and the chirps of a lemur.

Nestled against the banks of the Red River, the Double M Ranch and Rescue, with its high game fences and deer sprinkling the landscape,s its in stark contrast to the surrounding ranches.

“Having deer is kind of like eating potato chips- you can never actually have just one,” said McGovern with a laugh.

McGovern has several herds to take care of- fallow deer, axis deer, water buffalo, goats, and bison. In smaller numbers, there’s also a few kangaroos, a lemur, a potbelly pig, a pair of zebras, a watusi, and a few horses.

To read more, pick up a copy of the November edition of North Texas Farm & Ranch magazine, available digitally and in print. To subscribe by mail, call 940-872-5922.

-

Country Lifestyles2 years ago

Country Lifestyles2 years agoScott & Stacey Schumacher: A Growth Mindset

-

Country Lifestyles8 years ago

Country Lifestyles8 years agoStyle Your Profile – What your style cowboy hat says about you and new trends in 2017

-

HOME8 years ago

HOME8 years agoGrazing North Texas – Wilman Lovegrass

-

Outdoor10 years ago

Outdoor10 years agoButtercup or Primrose?

-

Country Lifestyles5 years ago

Country Lifestyles5 years agoAmber Crawford, Breakaway Roper

-

Country Lifestyles8 years ago

Country Lifestyles8 years agoDecember 2016 Profile, Rusty Riddle – The Riddle Way

-

Country Lifestyles9 years ago

Country Lifestyles9 years agoJune 2016 Profile – The man behind the mic: Bob Tallman

-

Equine1 year ago

Equine1 year agoThe Will to Win