Farm & Ranch

[AgriLife Today] Fossils fuel knowledge of future ecosystem needs

By: Kay Ledbetter

Writer: Kay Ledbetter, 806-677-5608, [email protected]

Contact: Dr. Michelle Lawing, 979-845-5033, [email protected]

COLLEGE STATION – In today’s rapidly changing world, successful conservation programs will need to look at fossils to effectively foster adaptive capacity in both historical and novel ecosystems, according to a Texas A&M AgriLife Research scientist.

Dr. Michelle Lawing, assistant professor in the ecosystem science and management department at Texas A&M University in College Station, was one of 41 experts covering this topic in their research article, “Merging paleobiology with conservation biology to guide the future of terrestrial ecosystems,” in the Feb. 10 issue of the journal Science.

“We use fossils to tell us how species responded to ancient climate change,” Lawing said. “There are many climate fluctuations in the past we can study to help us understand how species and communities coped with these changes.

“That past response helps us understand whether or not the measured modern response to environmental change is within the realm of normal or if it is greater than expected,” she said.

“For example, based on the fossil record, we know that communities typically reorganize after major environmental events, including extinction.”

Lawing joined others from around the world, including ecologists, conservation biologists, paleobiologists, geologists, lawyers, policy makers and nature writers, who do conservation and policy work on all continents, except Antarctica, to contribute to the Science article.

She said their research was based on conversations at a conference at the University of California-Berkeley in September 2015.

“That conference was a response to a growing need to get paleontologists, conservation biologists and policy makers in the same room to talk about what our areas of research can really bring to the table, in terms of conserving species in the face of changing climates,” Lawing said.

The conference was organized and funded in part by the Integrative Climate Change Biology Group, a subgroup of the International Union of Biological Sciences. Lawing is one of three group leaders of the Integrative Climate Change Biology initiative.

Other contributors included the Museum of Paleontology, Berkeley Initiative for Global Change Biology and the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research at the University of California-Berkeley; the Conservation Paleobiology Group at the department of biology, Stanford University; and the Senckenberg Biodiversity and Climate Research Centre, Frankfurt, Germany.

At Texas A&M, Lawing specializes in climate change biology, paleobiogeography and morphometrics. She explained she uses methods and models from modern ecology and evolutionary biology combined with evidence from the fossil record to create a better understanding of how species and communities respond to environmental change through time.

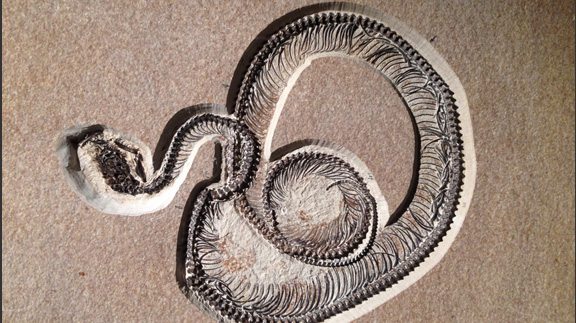

Her data was illustrated in the study to show how ecometrics might be used to monitor and measure ecosystem change through time, explaining that body proportions and proportions of certain bones are linked to land cover, land use and topography through locomotor performance.

An ecometric is a measurement used to characterize change across space and through time, from dozens of years to millions of years.

Lawing said in carnivoran communities, locomotor diversity can be measured by examining the limbs and ankles of the animals, which is known to be linked to vegetation cover. With snakes, the same relationship can be measured with the ratio of tail to body length.

Changes in these traits can be assessed for compatibility with changes in community composition and land cover, she said. For example, when land acquired by the University of Kansas was converted from agricultural grassland to forest between 1947 and 2006, turnover in the reptile life changed the overall community measurement of tail-to-body length. This change was also seen in grassland and forest ecosystems elsewhere.

Community snake tails, on average, are longer in forested areas because many snakes in the forest community have prehensile tails, meaning they use their tails like an appendage to grab branches to help stabilize their movement through the canopy.

Conversely, 19th-century deforestation of Indiana completely destroyed many large mammalian carnivores, resulting in a loss of locomotor diversity. She said this loss of locomotor diversity can be mapped to identify other regions that may have been similarly affected.

“As a group, we concluded that rapid global change means conservation biology has to be done differently going forward,” she said. “The fossil record has to be a critical part in guiding our efforts to conserve nature into the future.”

As a result of this study, Lawing said conservation biologists and paleobiologists are working together to develop new conservation paradigms for both historical and novel ecosystems.

“Instead of conserving ecosystems in their current or recent state, we need a more nuanced approach that involves figuring out which species and ecosystems need human intervention to persist, fostering connectivity of habitats with anticipation of future changes in climate and land use, and determining the compositional and functional variation that is expected within various ecosystems.”

Lawing said she will continue to develop ecometric tools to measure ecosystem changes through time and has helped organize another Integrative Climate Change Biology meeting March 6-8 in Nairobi, Kenya.

More information about the conference, “Traits Past, Present and Future: Quantitative Approaches to Paleontology, Conservation and Climate Change Biology in Africa,” can be found at http://iccbio.org/.

The complete Science journal article can be found at http://science.sciencemag.org/.

-30-

Find more stories, photos, videos and audio at http://today.agrilife.org

Farm & Ranch

Managing Show Cattle Through The Winter

By Heather Welper

Husband and wife duo, Heather and Calvin Welper, are the Co-Owners and Operators or Two C Livestock, located in Valley View, Texas.

The pair’s operation has a show cattle focus where they raise and sell purebred heifers of all breeds and club calf Hereford steers.

When it comes to show cattle, the Welpers know a thing or two including how to prepare for the cold winter months and the Texas major show season run.

To read more, pick up a copy of the November edition of North Texas Farm & Ranch magazine, available digitally and in print. To subscribe by mail, call 940-872-5922.

Farm & Ranch

Double M Ranch & Rescue

By Hannah Claxton, Editor

As the sun rises each day, so do the dozens of mouths that Meghan McGovern is responsible for getting fed. Rather than the sounds of a rooster crowing, McGovern hears the bellows and bleats of a variety of exotic deer, the chortle of kangaroos, the grunts of water buffaloes, and the chirps of a lemur.

Nestled against the banks of the Red River, the Double M Ranch and Rescue, with its high game fences and deer sprinkling the landscape,s its in stark contrast to the surrounding ranches.

“Having deer is kind of like eating potato chips- you can never actually have just one,” said McGovern with a laugh.

McGovern has several herds to take care of- fallow deer, axis deer, water buffalo, goats, and bison. In smaller numbers, there’s also a few kangaroos, a lemur, a potbelly pig, a pair of zebras, a watusi, and a few horses.

To read more, pick up a copy of the November edition of North Texas Farm & Ranch magazine, available digitally and in print. To subscribe by mail, call 940-872-5922.

Farm & Ranch

Acorn Toxicity

By Barry Whitworth, DVM, MPH

With the prolonged drought, most pastures in Oklahoma end up in poor condition. With the lack of available forage, animals may go in search of alternative foods.

If oak trees are in the pastures, acorns may be a favorite meal for some livestock in the fall. This may result in oak poisoning.

Oak leaves, twigs, buds, and acorns may be toxic to some animals when consumed.

To read more, pick up a copy of the November edition of North Texas Farm & Ranch magazine, available digitally and in print. To subscribe by mail, call 940-872-5922.

-

Country Lifestyles2 years ago

Country Lifestyles2 years agoScott & Stacey Schumacher: A Growth Mindset

-

Country Lifestyles8 years ago

Country Lifestyles8 years agoStyle Your Profile – What your style cowboy hat says about you and new trends in 2017

-

HOME8 years ago

HOME8 years agoGrazing North Texas – Wilman Lovegrass

-

Outdoor10 years ago

Outdoor10 years agoButtercup or Primrose?

-

Country Lifestyles5 years ago

Country Lifestyles5 years agoAmber Crawford, Breakaway Roper

-

Country Lifestyles9 years ago

Country Lifestyles9 years agoJune 2016 Profile – The man behind the mic: Bob Tallman

-

Country Lifestyles8 years ago

Country Lifestyles8 years agoDecember 2016 Profile, Rusty Riddle – The Riddle Way

-

Equine1 year ago

Equine1 year agoThe Will to Win