Farm & Ranch

[AgriLife Today] Livestock guardian dogs come to area ranches

By: Steve Byrns

Year-long project involves seven ranches, 22 dogs

Writer: Steve Byrns, 325-653-4576, s-byrns@tamu.edu

Contact: Dr. Reid Redden, 325-653-4576, reid.redden@ag.tamu.edu

SAN ANGELO – The West Texas sheep and goat industry will soon be “going to the dogs” if a team of Texas A&M AgriLife experts has their way.

Dr. Reid Redden and Dr. John Tomecek, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service state sheep and goat specialist and wildlife specialist, respectively, and Dr. John Walker, Texas A&M AgriLife Research resident director, all of San Angelo, are heading a new year-long research project called “Understanding and Expanding the Use of Livestock Guardian Dogs in West Texas.”

“The goal is to place livestock guardian dogs on large West Texas ranches with ranchers who have never used them as a predator management tool,” Redden said.

Redden said 22 dogs, including two backups, arrived shortly after Jan. 1 from a professional livestock guardian dog breeder based in Montana. The dogs, specifically bred and raised to live with and guard sheep and goats, are composite crossbred animals comprised of five large breeds of dogs used for thousands of years for this purpose.

“Predation on sheep and goats on large West Texas operations is arguably that industry’s biggest problem,” Redden said. “For many ranchers, controlling predators has gotten to the point where it’s almost impossible to effectively conduct predator management by traditional lethal means. So we are looking at new tools for our area, and livestock guardian dogs are a tool that’s been used in other countries and elsewhere in the U.S., but it has not been used very much in West Texas. The main difference is management style, and this management style affects how the dogs work.”

Redden said the research project aims to investigate and work with cooperating ranchers, located from San Angelo west to Iraan and down to Del Rio, to better understand how livestock guardian dogs work in large expansive pastures.

“We have pastures in the project from between 500 and 5,000 acres,” Redden said. “These are large pastures where sheep can get scattered, making it easier for predators to do damage to the flock. It’s also difficult to spot a problem quickly in a large pasture, especially if it’s rough, brushy country as many West Texas pastures are.”

Redden said the dogs were placed with seven cooperators and on AgriLife property Walker directs. Some ranchers got two dogs and some got four. The dogs, all between six and ten months old and previously bonded with sheep, were placed on the ranches shortly after Jan. 1. Once the dogs were placed on an operation, they were put in a small pen to bond with the sheep on that operation. Then within a few days to a few weeks, they were put out into large pastures.

Throughout the year the dogs are being fitted with GPS collars to track their movements throughout the day and night to see how they are working as a predator management tool.

“The observations thus far on the project have been fairly positive,” Redden said. “Most of the cooperators we’ve talked to have had good luck with the guard dogs. There have been a few issues that needed to be addressed, which is common with guardian dogs. It requires effort and perseverance to make the program work. But we have not had any reported sheep losses from coyotes, the No. 1 predator in Texas.

“One rancher even commented since getting the dogs that he’s seeing ‘repeat appearances’ among his sheep. Before, when his ewes would leave with a lamb, many of those lambs were never seen again, but now he is seeing them again…thus they are making repeat appearances.

“Based on cooperator reports, the guardian dogs have changed the movement patterns among the predators. Overall, we think they are starting to show some real positive effects on all the ranches that we’ve put them on.”

The other part of the project Tomecek oversees centers around the use of game cameras left running throughout the year to measure the traffic of predators such as coyotes, foxes and feral hogs.

Tomecek noted the predator populations were camera-surveyed prior to the livestock guardian dogs being added and will continue to be surveyed throughout the year to understand how the dogs change the predator movement and patterns as the dogs move in and around the ranches.

“Primarily, these livestock guardian dogs are a tool that dissuade predators from getting in the livestock,” Redden said. “One of the things people think is that the dogs are aggressive and go out and kill predators, and that is very rare. Actually the dogs are bonded to the sheep, they stay with them. They are part of the flock, while at the same time they provide protection for the sheep.

“They bark throughout the night to warn predators to avoid the area. They dissuade them from harming the livestock, and the predators go back to their normal prey of mostly rabbits and other small rodents.”

Redden said from a personal standpoint that livestock guardian dogs have kept his family-owned sheep and goat operation going since the 1990s.

“They’re a fantastic tool,” he said. “They do take effort and work to get them implemented and bonded and working on the ranch. But I think it’s a fantastic return on the investment of time and money once guardian dogs are put into place and you understand how to use them and understand how they work. The peace of mind that predation is no longer a problem is the best benefit of all.”

The AgriLife team would like to see the program build industry knowledge and widespread acceptance of livestock guardian dogs. They hope the group of ranchers will evolve into livestock guardian dog ambassadors, willing to help others wanting to use the dogs to remain economically viable in the sheep and goat industry.

“The whole West Texas belief that loose dogs among sheep as always being a bad thing must change, because these dogs don’t behave as most dogs do and must be handled in a totally unique manner,” he said. “It will be a learning experience, not only for the producers involved with this work, but for the whole West Texas ranching community as well.”

For more information on livestock guardian dogs, go to http://sanangelo.tamu.edu/files/2013/08/Livestock-Guardian-Dogs1.pdf . Redden can be reached at 325-653-4576, extension 224 or reid.redden@ag.tamu.edu .

-30-

LikeTweet

Find more stories, photos, videos and audio at http://today.agrilife.org

Farm & Ranch

What to expect when your cow’s expecting

Overweight cattle and cattle turned out on lush legumes with high concentration are at risk as well. In this case, an epidural anesthetic is usually necessary. The tissue will need to be replaced and sutured in place. Vaginal sutures will need to be removed prior to calving.

Toxemia happens when cattle are exposed to low nutrition during the last two months of pregnancy. Cows that are overly fat and/or carrying twins are at higher risk. Cows with toxemia become depressed, stop eating and often stand off away from the herd. You will notice some have the scent of acetone on their breath. As the condition worsens, the cow may develop muscle tremors. Treatment for toxemia is IV glucose, B vitamins or propylene glycol given by oral drench.

During calving there are a number of problems that could occur. Those include dystocia, bruises and lacerations to the birth canal, uterine prolapse, milk fever, retained placenta and grass tetany.

According to the Beef Cattle Handbook, a product of Extension Beef Cattle Resource Committee Adapted from the Cattle Producer’s Library, at any time a cow is unable to deliver her calf, a dystocia has occurred. There are many things a producer can do to reduce this incidence. With heifers, lot those with small pelvic areas before breeding. Select bulls based on their birth weight, not on their relative size. Ultimately use bulls that will produce small birth-weight calves. When calving first-calf heifers separate them from cows, at best into small groups. Producers will want to provide surveillance over the heifers on a 24 hour basis. Some tips include restricting the calving to 42 to 60 days. That will enable personal focus for a short, intense calving period. Also feeding at night between 9 and 11 p.m. will cause more animals to calve during daylight hours.

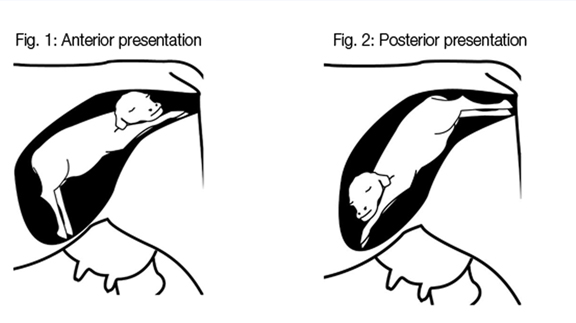

If problems arise and a cow hasn’t shown progress in 60 to 90 minutes, it’s time for the producers to step in. Signs of an abnormal delivery are the head only, the head and one leg, one leg alone or the tail. At this point it is best to contain the animal in a squeeze chute or small pen. A calf can only deliver one of two ways: both front feet followed by the head or both back feet out together. Once constrained, using ample lubrication, a producer can reach in and move the calf to one of the two correct positions. If unable to do so, a veterinarian should be called. The top problems include not getting the head out with front feet, having a calf too big to deliver through the mother’s birth canal resulting in hip lock and abnormal breach in which the tail is the only part of the calf visible through the vulva. If all goes well and pulling the calf is suggested, direct traction down and away from the birth canal. Do not pull straight out behind the cow. If two men are unable to pull the calf using the OB chains or when using the calf puller, do not use excessive force. It will not deliver the calf. Odds are the cows birth canal is too small for the calf and will result in a c-section.

Keep in mind bruises, lacerations and rupture of the birth canal are possible during a difficult birth. Rough handling of the calf or maternal tissues and careless use of obstetrical instruments during calving add danger. This is typical when a cow is in labor several hours with a dry, non-lubricated birth canal.

Cows with difficult delivery and trauma to the tissue and birth canal may have damage to the nerves and spinal cord or hips that supply the legs. This results in abnormal leg function. In some cases, while pulling a calf, excessive force was used and the middle lower pelvis bones were fractured. At this point steroids are administered to help with swelling and nerve healing. In bad cases were the cows are unable to stand, they need to be hoisted to their feet twice a day.

In older cows producers may see difficulty in birth injury or irritation of the external birth canal and severe straining, retained placenta and loose uterine attachment in the abdominal cavity called uterine prolapse. When noticed, this condition needs immediate action. Apply material to uterine wall to saturate fluid ASAP. You can use sulfaurea powder, urea powder or even sugar. Replace the uterus immediately or call your veterinarian. Without properly replacing the uterine horns, prolapse will reoccur.

Usually the placenta is passed in three to eight hours. If the placenta hasn’t passed in eight to 12 hours of calving, the placenta is retained and the cows must be treated. A number of reasons lead to retained placenta: dystocia, c-sections, fetotomy, twinning or abortion along with other infectious diseases. Even feed deficiencies, malnutrition, low carotene, vitamin A, iodine, selenium and vitamin E can be to blame. To treat, use slight, manual force and gently pull on the placenta. If it resists, stop and pack the uterus with boluses or fluid douches to keep antibiotics in the uterus. As with prolapse, be sure to use proper hygiene when treating the uterus or worse problems will occur.

Another condition parallel with cows with age, number of calves and dairy or mixed breeds is milk fever. This condition happens when a cow starting to produce milk is unable to remove calcium from her bones quickly enough. If blood levels of calcium fall below the minimal level, the muscles of the body are unable to function. This leaves the cow almost crippled, comatose and dead. High blood levels of estrogen inhibit calcium mobilization; this may be a factor on pastures that are high in legumes. Usually a slow administer of IV calcium is given. 300 to 500 ml of a commercial calcium solution is given over 20 to 30 minutes.

Lastly, grass tetany poses as an issue to cows calving. It is similar to milk fever, but in this instance cattle have heavy post-calving lactation and lose large amounts of magnesium in their milk. Most types of mixed pasture grasses are low in magnesium. If cows are exposed to cold weather or stress during early lactation, their blood levels may drop low enough to cause grass tetany. At that point an IV of magnesium is given with calcium. Treatment is not as effective as with milk fever and in many cases, animals do not respond.

This article was originally published in the January 2016 issue of North Texas Farm & Ranch.

Farm & Ranch

Managing Show Cattle Through The Winter

By Heather Welper

Husband and wife duo, Heather and Calvin Welper, are the Co-Owners and Operators or Two C Livestock, located in Valley View, Texas.

The pair’s operation has a show cattle focus where they raise and sell purebred heifers of all breeds and club calf Hereford steers.

When it comes to show cattle, the Welpers know a thing or two including how to prepare for the cold winter months and the Texas major show season run.

To read more, pick up a copy of the November edition of North Texas Farm & Ranch magazine, available digitally and in print. To subscribe by mail, call 940-872-5922.

Farm & Ranch

Double M Ranch & Rescue

By Hannah Claxton, Editor

As the sun rises each day, so do the dozens of mouths that Meghan McGovern is responsible for getting fed. Rather than the sounds of a rooster crowing, McGovern hears the bellows and bleats of a variety of exotic deer, the chortle of kangaroos, the grunts of water buffaloes, and the chirps of a lemur.

Nestled against the banks of the Red River, the Double M Ranch and Rescue, with its high game fences and deer sprinkling the landscape,s its in stark contrast to the surrounding ranches.

“Having deer is kind of like eating potato chips- you can never actually have just one,” said McGovern with a laugh.

McGovern has several herds to take care of- fallow deer, axis deer, water buffalo, goats, and bison. In smaller numbers, there’s also a few kangaroos, a lemur, a potbelly pig, a pair of zebras, a watusi, and a few horses.

To read more, pick up a copy of the November edition of North Texas Farm & Ranch magazine, available digitally and in print. To subscribe by mail, call 940-872-5922.

-

Country Lifestyles2 years ago

Country Lifestyles2 years agoScott & Stacey Schumacher: A Growth Mindset

-

Country Lifestyles8 years ago

Country Lifestyles8 years agoStyle Your Profile – What your style cowboy hat says about you and new trends in 2017

-

HOME8 years ago

HOME8 years agoGrazing North Texas – Wilman Lovegrass

-

Outdoor10 years ago

Outdoor10 years agoButtercup or Primrose?

-

Country Lifestyles9 years ago

Country Lifestyles9 years agoJune 2016 Profile – The man behind the mic: Bob Tallman

-

Country Lifestyles8 years ago

Country Lifestyles8 years agoDecember 2016 Profile, Rusty Riddle – The Riddle Way

-

Country Lifestyles5 years ago

Country Lifestyles5 years agoAmber Crawford, Breakaway Roper

-

Horsefeathers11 years ago

Horsefeathers11 years agoMount Scott: Country Humor with David Gregory