HOME

AgriLife Research investigators study effects of aflatoxins on quail reproduction

By: Paul Schattenberg

UVALDE – In an effort to discover find what’s causing the decline of Texas wild quail populations, Texas A&M AgriLife Research scientists investigated whether regular ingestion of low levels of aflatoxins by bobwhite and scaled quail may impacttheir ability to reproduce.

VIDEO: Quail and Afaltoxin Study: https://youtu.be/KV1r1ZONWDE

“In trying to identify reasons behind the decline in quail populations in Texas, we determined it would be worthwhile to study whether aflatoxins, which are fungal toxins that contaminate grain, might be a concern,” said Dr. Susan Cooper, AgriLife Research wildlife ecologist at the Texas A&M AgriLife Research and Extension Center in Uvalde.

“We wondered whether eating grain-based feed supplements for wildlife, especially deer corn, might possibly expose quail to chronic low levels of aflatoxin poisoning, thereby affecting their reproductive ability.”

Cooper was helped in the study by research assistant Shane Sieckenius and research technician Andrea Silva, both of AgriLife Research in Uvalde.

Cooper said previous research has shown acute dosages of 100 parts per billion of aflatoxin in poultry could cause liver damage or dysfunction, leading to ill health as well as reduced egg production and hatchability.

In wild quail, such effects would result in a decrease in reproductive output and reduction in quail population, she said.

“We knew that experimental doses of even small amounts of aflatoxins may cause liver damage and immunosuppression,” Cooper explained. “So the objective of this study was to determine whether consumption of aflatoxins in feed at those levels likely to be encountered as a result of wild quail eating supplemental feed provided for quail, deer or livestock, would result in a reduction in their reproductive output.”

The researchers conducted feeding trials using 30 northern bobwhites and 30 scaled quail housed in breeding pairs. They initially conducted free-choice trials on three replicate pairs of each type of quail to determine if they could detect the presence of aflatoxin in their feed. The birds could not detect and avoid aflatoxins.

Then for 25 weeks, encompassing the breeding season of March through August, the researchers divided the remaining quail into four groups of three pairs of each species. These 12 pairs of caged northern bobwhites and 12 pairs of scaled quail were fed diets that included twice weekly feedings of 20 grams of corn. The corn had either 0, 25, 50 or 100 parts per billion of aflatoxin B1 added to it prior to consumption by the quail.

“These amounts of aflatoxin — 25, 50 and 100 parts per billion — represented the recommended maximum levels for bird feed and legal limits for wildlife and livestock feed respectively,” Cooper said. “And the feeding schedule mimicked what would occur with wild quail periodically visiting a source of supplemental feed.”

Quail were weighed monthly to see if there was any weight change due to the consumption of grain-based feed with low-level amounts of aflatoxion. (Texas A&M AgriLife Research photo)

The researchers measured any changes in reproductive output and quail health over the six-month breeding period. Reproductive output was measured in terms of number of eggs produced per week as well as the weight of the eggs and their yolks. Health changes were measured by the amount of food consumed by the quail on a weekly basis and by any reduction in weight as measured on a monthly basis.

“We had to extract the birds from the pens using butterfly nets, then put them into a small enclosed cage area to weigh them,” said Sieckenius, who also prepared the corn for adding the aflatoxin. “We collected eggs daily and hard-boiled the eggs collected on the last week of each month to extract the yolks so we could accurately measure their weight.”

Cooper said the results of the study showed intermittent consumption of aflatoxin-contaminated feed had no measurable effect on the body weight, feed consumption and visible health of either species of quail.

“The reproductive output, measured by number of eggs produced, egg weight and yolk weight, was also unaffected,” she said. “Thus, in the short term, it appears that chronic low-level exposure to aflatoxins has no measurable deleterious effects on the health and productivity of quail.”

Cooper said as a result of the study it was possible to conclude that aflatoxins in supplemental feed are unlikely to be a factor contributing to the long-term population decline of northern bobwhite and scaled quail through reduced health or egg production. However, she cautioned that feed should be kept dry to avoid potential contamination with higher levels of aflatoxin that may be harmful.

”This project also does not address any long-term effects of aflatoxin consumption that may become evident when wild quail are exposed to nutritional or environmental stresses,” she said.

-30-

LikeTweet

Find more stories, photos, videos and audio at http://today.agrilife.org

Attractions

The Deadliest Prairie in Texas

By Shannon Gillette

The Salt Creek Prairie with its rolling natural grasses and rampant wildflowers was a deceptive backdrop to the most dangerous prairie in Texas. Located in the northern section of Young County, the prairie absorbed an abundant amount of blood, shed from the battles between the encroaching white man and the Indians desperately trying to hold on to their home lands.

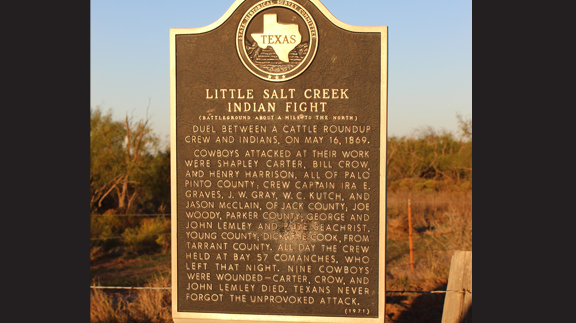

The Salt Creek Prairie was the location of several encounters between the Kiowa, Comanche and the area ranchers. The Indian Raid of Elm Creek on Oct. 13, 1867, resulted in the death of seven ranchers, five former Confederate Soldiers, the kidnapping of six women and children and the theft of 10,000 head of cattle. On May 18, 1871, the prairie witnessed another massacre when the Warren Wagon Train was hit by Kiowa under the command of Satanta, Satank and Big Tree. Seven members of the wagon train were murdered and forty-one mules stolen. But perhaps one of the bloodiest encounters was the Salt Creek fight on May 16, 1869.

Eleven cowboys under the watchful eye of their foreman, Captain Ira Graves were in the process of rounding up about five hundred head of their cattle about five miles southeast of present day Olney, Texas. The ranch hands were William Crow, John and George Lemley, C. L. Carter, Jason McClain, W. C. Kutch, J. W. Gray, Henry Harrison, Rube Secris, Joe Woody and a former slave known as Dick. They had noticed signs of recent Indian activity and were vigilant as they gathered the herd together. Each was armed with cap and ball six shooters. They had pointed the cattle towards the ranch and had made about four miles headway when they noticed a few more head grazing in the distance. Graves sent Carter and Kutch to gather them up. They had advanced about two miles when they spotted a large band of Indians approaching fast. Carter and Kutch could have taken cover in the sparse timber, but realized they would be leaving their companions in serious danger. The two groups met in the middle and tried to take cover in a small ravine that drained into the Salt Creek. The shallow-make shift fox hole offered very little protection.

The Indians attacked again and again. Arrows rained down on the cowboys in a continuous stream of painful blows. They attacked and retreated and attacked and retreated, but each time were met with volleys of gunfire from the small group of ranch hands. Each time the Indians retreated, they conferenced with their leader, who had stationed himself on a small hill away from the battle. After six hours of the constant onslaught, Graves developed a plan. When the Indians retreated, he ordered his men to stand and wave as wildly as they possibly could. The band of Indians, numbering over fifty strong, retreated for a final time, leaving the small band of cowboys alone.

As the dust settled the ranch hands evaluated their losses. In Kutch’s personal account given several years later, he described the aftermath: “Wm. Crow had been dead for several hours, and C. L. Carter had a severe arrow wound in his body, and had been also painfully injured with a rifle ball. John Lemley was mortally wounded in the abdomen with an arrow; J. W. Gray had been twice struck with rifle balls, once in the body and one in the leg; W. C. Kutch had two arrow heads in his knee and one in his shoulder; Jason McClain had been twice wounded with arrows; Rube Secris had his mouth badly torn, and his knee shattered; Geo Lemley had his face badly torn, and an arrow wound in his arm; and Ira Graves and Dick were also wounded.” Harrison was sent to Harmison Ranch for help.

The exhausted and wounded cowboys braved a very long and frightful night. With great relief, the morning hours brought the welcome sight of an incoming wagon. The rescuers patched the wounded as well as they could and sent word that doctors were needed desperately. The doctors did not arrive until a full twenty-four hours later. Carter passed away the next day from the injuries received during the battle. Two years later, McClain died while on another cattle drive. The cause of his death was blamed on the substantial injuries incurred on that fateful day in 1869.

While today the prairie grasses still wave and the wildflowers bloom in gorgeous arrays of colors nestled between cactus and mesquite, the blood shed is a distant memory. On crisp spring mornings it is easy to picture the deadly predicament that the cowboys faced.

This article originally appeared in the January 2016 issue of NTFR.

HOME

Preparing Spring Gardens

By Hannah Claxton | Editor

The North Texas area is located within USDA Hardiness zones seven and eight. The zones are categorized by predicted low temperatures for winter and timing of the first and last frosts.

Zone seven usually has winter low temps between 0 and 10 degrees F with the average date of the first frost falling between Oct. 29 and Nov. 15 and the average date of the last frost falling between March 22 and April 3.

Overall, these two zones have similar climates and growing conditions, making the options for timing and variety within a garden very similar.

In these zones, cool-season crops should go in the ground in March, meaning that soil preparation should start now.

To read more, pick up a copy of the January edition of North Texas Farm & Ranch magazine, available digitally and in print. To subscribe by mail, call 940-872-5922.

HOME

Equine Vaccinations

By Heather Lloyd

Vaccinations are a critical component of maintaining the health and well-being of horses, especially in environments where they are exposed to other animals, such as in the sport, show and performance arenas. Horses, like all animals, are susceptible to various infectious diseases that can spread quickly and cause serious harm.

A routine vaccination schedule helps prevent the spread of these diseases by preparing the horse’s immune system.

To read more, pick up a copy of the November edition of North Texas Farm & Ranch magazine, available digitally and in print. To subscribe by mail, call 940-872-5922.

-

Country Lifestyles2 years ago

Country Lifestyles2 years agoScott & Stacey Schumacher: A Growth Mindset

-

Country Lifestyles8 years ago

Country Lifestyles8 years agoStyle Your Profile – What your style cowboy hat says about you and new trends in 2017

-

HOME8 years ago

HOME8 years agoGrazing North Texas – Wilman Lovegrass

-

Outdoor10 years ago

Outdoor10 years agoButtercup or Primrose?

-

Country Lifestyles5 years ago

Country Lifestyles5 years agoAmber Crawford, Breakaway Roper

-

Country Lifestyles8 years ago

Country Lifestyles8 years agoDecember 2016 Profile, Rusty Riddle – The Riddle Way

-

Country Lifestyles9 years ago

Country Lifestyles9 years agoJune 2016 Profile – The man behind the mic: Bob Tallman

-

Equine1 year ago

Equine1 year agoThe Will to Win