Farm & Ranch

[AgriLife Today] Soil water storage, new varieties critical to wheat production

By: Kay Ledbetter

Writer: Kay Ledbetter, 806-677-5608, [email protected]

Contact: Dr. Qingwu Xue, 806-354-5803, [email protected]

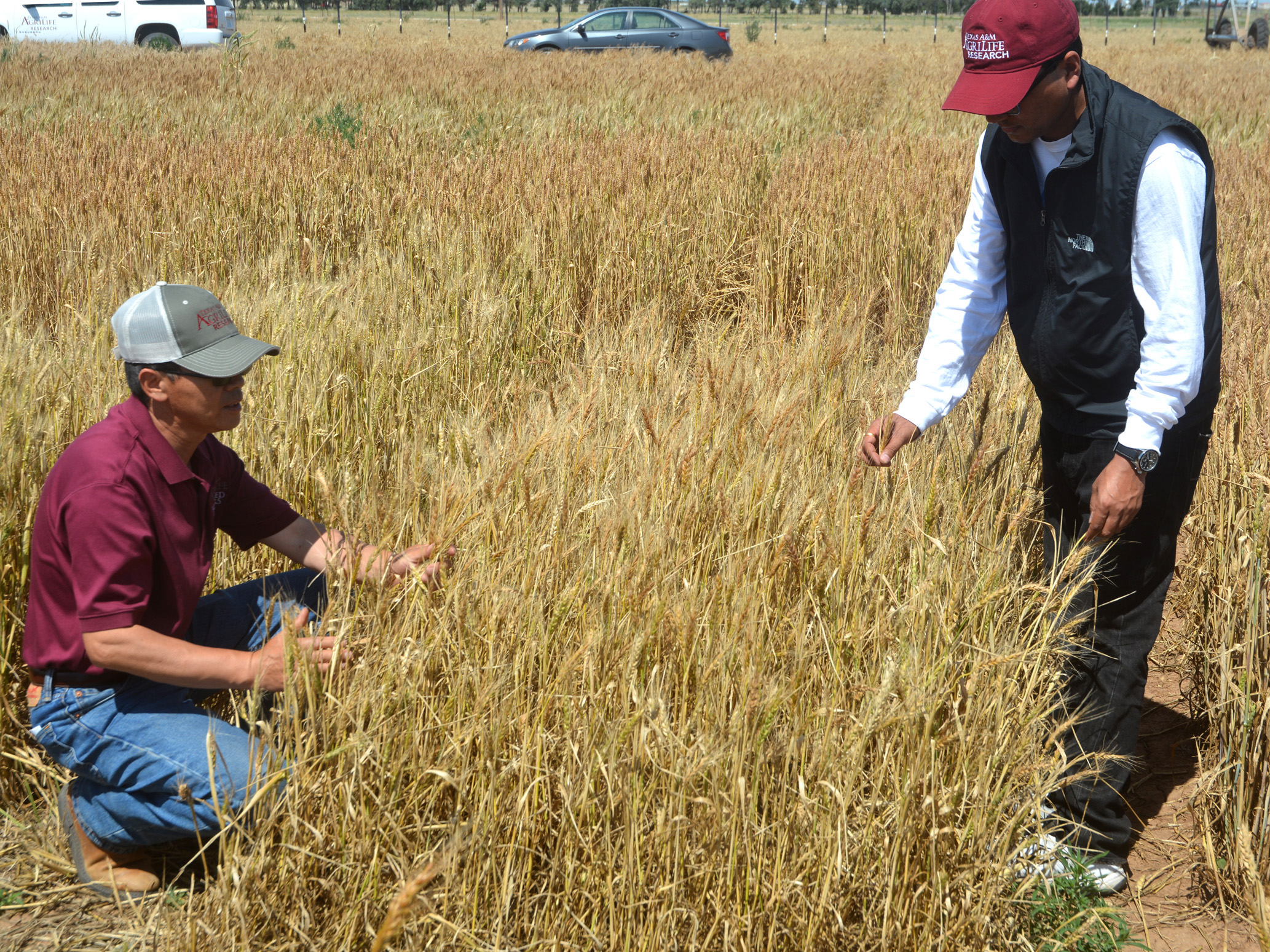

AMARILLO – Regardless of what watering regimen a producer might have on wheat, in the High Plains it is critical that new varieties are grown to maximize yields, according to a long-running study by Texas A&M AgriLife Research.

“The overall objective of our program is to better understand the physiological responses of different wheat genotypes to drought stress and water-limited conditions,” Xue said. “We have an overall goal to improve the water-use efficiency and yields of wheat.”The purpose of this study is to show how different varieties of wheat respond to different levels of water, said Dr. Qingwu Xue, AgriLife Research crop stress physiologist in Amarillo.

Utilizing a center-pivot irrigation system, he has been growing the top 20 varieties for the High Plains under three to five different water treatments ranging from dryland to limited and full irrigation since 2011. The physiology group works with Dr. Jackie Rudd, wheat breeder, and Dr. Shuyu Liu, small grain geneticist, both with AgriLife Research in Amarillo.

“We want to identify the best management practices and genotypes in these environments to recommend to producers that will help them optimize their water use,” Xue said.

“So far, what we have found is effective water use is still very important, especially under limited-water conditions. Dr. Sushil Thapa, the post-doctoral scientist working in our group, has summarized field data for the last five wheat growing seasons at Bushland.

“We are looking at the soil-water dynamics in different varieties developed from the 1970s to the most recent and how the soil-water extraction is correlated to yield and yield components,” Xue said. “What we found is the newer varieties have better capability to utilize soil water.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7fEDnEg057k&feature=youtu.be

Wheat needs to be able to access and utilize stored soil water, seasonal rainfall and any irrigation water to get higher yields, Xue and Thapa said.

They found the wheat was using water only from the 3-4 foot soil profile in the dry season of 2011. In contrast, the wheat plots harvested in 2016 were able to use the water from 6-8 feet.

“That’s very important when you look at the roots and the soil-water dynamics,” Xue said. “In very dry seasons, the roots cannot go deep enough to take advantage of the water.”

That is why it is also important to take care of the above-ground growth, he said. The newer varieties have better and more vigorous early growth, which means they have more above-ground biomass and better ground cover in the early stage. This also helps to improve the root mass as well as the rooting depth.

Over the last 30 or 40 years, breeding has improved wheat’s capability to access soil water stored during the fallow period and the water from seasonal rainfall.

They found the newer varieties are especially able to access the deeper water.

TAM 105, developed in the 1970s, produced a smaller head in the field trial. (Texas A&M AgriLife photos by Kay Ledbetter)

“We specifically looked at TAM 105 compared to TAM 111 and TAM 112,” Xue said. “Comparing those three varieties, the two newer varieties always had a better ability to extract water from the deeper soil.” The best way to improve soil-water storage is allowing for sufficient fallow periods with good residue management, Xue said.

TAM 112, which was developed more recently, had a large head under the same growing conditions. (Texas A&M AgriLife photos by Kay Ledbetter)

With good soil moisture, the newer varieties will produce more forage and establish a better root system in the early stages of growth, Thapa said.

“While many producers may think about forage only for cattle grazing, it is also important for yield potential as it is a good indicator that a strong root system is being developed,” Xue said

Xue provided an example of how the varieties make a difference. In an extreme drought year like 2011, TAM 105, developed in the 1970s, yielded only 8 bushels per acre. TAM 111 and TAM 112, developed more recently, yielded 10 bushels per acre under dryland conditions.

“In a wet year like 2016, the variety difference was even more significant,” he said. “With the older varieties, you’re looking at around 40 bushels per acre. But the newer varieties like TAM 114 yielded 60 bushels per acre. So if you can get 10 to 20 bushels per acre difference over a large area that’s a big difference.”

Xue said using the newer varieties with the ability to produce more forage early and thus deeper roots will help, but the field must have good soil water to start with, even on dryland, or it might be well to let the field lay fallow for a longer time.

“In this environment, if you don’t have good ground cover and good forage in the early stages of wheat, you probably don’t have a good chance to obtain the higher grain yield, given a highly variable seasonal rainfall,” he said.

For years with exceptional water, he suggested producers consider putting nitrogen on their wheat field to help early growth and the ability to utilize deep soil moisture.

Also, producers who know their wheat will have adequate water need to consider the newer varieties with disease-resistance traits, he said.

“That was especially significant this year when we saw a lot of wheat streak mosaic virus damage on some varieties and much less on others,” Xue said.

-30-

Find more stories, photos, videos and audio at http://today.agrilife.org

Farm & Ranch

Managing Show Cattle Through The Winter

By Heather Welper

Husband and wife duo, Heather and Calvin Welper, are the Co-Owners and Operators or Two C Livestock, located in Valley View, Texas.

The pair’s operation has a show cattle focus where they raise and sell purebred heifers of all breeds and club calf Hereford steers.

When it comes to show cattle, the Welpers know a thing or two including how to prepare for the cold winter months and the Texas major show season run.

To read more, pick up a copy of the November edition of North Texas Farm & Ranch magazine, available digitally and in print. To subscribe by mail, call 940-872-5922.

Farm & Ranch

Double M Ranch & Rescue

By Hannah Claxton, Editor

As the sun rises each day, so do the dozens of mouths that Meghan McGovern is responsible for getting fed. Rather than the sounds of a rooster crowing, McGovern hears the bellows and bleats of a variety of exotic deer, the chortle of kangaroos, the grunts of water buffaloes, and the chirps of a lemur.

Nestled against the banks of the Red River, the Double M Ranch and Rescue, with its high game fences and deer sprinkling the landscape,s its in stark contrast to the surrounding ranches.

“Having deer is kind of like eating potato chips- you can never actually have just one,” said McGovern with a laugh.

McGovern has several herds to take care of- fallow deer, axis deer, water buffalo, goats, and bison. In smaller numbers, there’s also a few kangaroos, a lemur, a potbelly pig, a pair of zebras, a watusi, and a few horses.

To read more, pick up a copy of the November edition of North Texas Farm & Ranch magazine, available digitally and in print. To subscribe by mail, call 940-872-5922.

Farm & Ranch

Acorn Toxicity

By Barry Whitworth, DVM, MPH

With the prolonged drought, most pastures in Oklahoma end up in poor condition. With the lack of available forage, animals may go in search of alternative foods.

If oak trees are in the pastures, acorns may be a favorite meal for some livestock in the fall. This may result in oak poisoning.

Oak leaves, twigs, buds, and acorns may be toxic to some animals when consumed.

To read more, pick up a copy of the November edition of North Texas Farm & Ranch magazine, available digitally and in print. To subscribe by mail, call 940-872-5922.

-

Country Lifestyles2 years ago

Country Lifestyles2 years agoScott & Stacey Schumacher: A Growth Mindset

-

Country Lifestyles8 years ago

Country Lifestyles8 years agoStyle Your Profile – What your style cowboy hat says about you and new trends in 2017

-

HOME8 years ago

HOME8 years agoGrazing North Texas – Wilman Lovegrass

-

Outdoor10 years ago

Outdoor10 years agoButtercup or Primrose?

-

Country Lifestyles5 years ago

Country Lifestyles5 years agoAmber Crawford, Breakaway Roper

-

Country Lifestyles9 years ago

Country Lifestyles9 years agoJune 2016 Profile – The man behind the mic: Bob Tallman

-

Country Lifestyles8 years ago

Country Lifestyles8 years agoDecember 2016 Profile, Rusty Riddle – The Riddle Way

-

Equine1 year ago

Equine1 year agoThe Will to Win